Japanese Tattoo: The Ultimate Guide to Irezumi, its Motifs and their Meaning (2026)

- DAI YOKAI

- Feb 14

- 13 min read

Somewhere in 18th-century Japan, an Edo fireman removes his kimono in front of his comrades. His entire back is a living mural: a blue dragon coiled in waves of black ink, a screaming Hannya mask on his shoulder, scarlet peonies bursting forth on his ribs. No one flinches. It is his invisible armor. His identity etched into his flesh.

Today, millions of people around the world wear Japanese designs without always knowing their true meaning. A dragon tattooed upside down. A koi carp swimming the wrong way. An oni mixed with autumn cherry blossoms. Each mistake tells a story the wearer didn't choose.

This guide exists for that very reason. My name is Jeremy, I'm a craftsman of Japanese folklore at Dai Yokai , and I literally have Japan in my blood. Before sculpting masks, I spent countless hours studying Yokai—the same ones that have fueled Irezumi for three centuries. Here, I dissect every motif, every rule of composition, every taboo.

What is a Japanese Tattoo (Irezumi)?

A traditional Japanese tattoo, called Irezumi (入れ墨, "inserting ink") or Horimono (彫り物, "carved thing"), is a codified body composition that covers large areas of the body, incorporating Japanese mythological motifs (dragons, demons, carp) into a continuous background of waves, clouds, and wind. Unlike Western tattoos where the motifs are isolated, Irezumi forms a unique narrative mural that follows the wearer's musculature.

For a complete dive into the history of this art — from the Dogū figurines of the Jōmon period to the Meiji bans — see my dossier dedicated to Irezumi and Horimono .

Irezumi, Horimono, Wabori: What's the Difference?

Before going any further, we need to establish the vocabulary. In Japan, the word you use to say "tattoo" changes how you are perceived.

Term | Kanji | Literal meaning | Connotation | Use |

Irezumi | 入れ墨 | "Insert ink" | Neutral to pejorative (historically punitive) | Most common generic term |

Horimono | 彫り物 | "Sculpted/engraved thing" | Noble, artistic | Preferred by master tattoo artists (Horishi) |

Wabori | 和彫り | "Japanese engraving" | Traditional technique | Refers to the Japanese style (vs. Western) |

Yobori | 洋彫り | "Western engraving" | Neutral | Western-style tattoos in Japan |

Tebori | 手彫り | "Hand engraving" | Respectful, handcrafted | Manual technique (vs. machine) |

Bokkei | 墨刑 | "Punishment by ink" | Shameful | Punitive tattooing of criminals (7th–19th centuries) |

My advice as a craftsman: if you're speaking to a Japanese Horishi, use "Horimono." It's the word that shows you respect their art. "Irezumi" is correct but more neutral. Never say "Tattoo" ( Tatū in Japanese) when referring to a traditional bodysuit—that's reserved for small Western designs.

The Technique: Tebori vs. Machine

Japanese tattooing is distinguished first and foremost by its ancient technique: Tebori (手彫り). Instead of an electric tattoo machine that vibrates at 150 pulses per second, the master tattoo artist (Horishi) uses a wooden or metal handle (Nomi) to which a bundle of needles is attached. With a rhythmic movement of the wrist, they insert the ink under the skin stroke by stroke. The characteristic sound— sha-sha-sha —is the sonic signature of this art.

Criteria | Tebori (Main) | Machine (Dermograph) |

Speed | Slow (2 to 5 times longer) | Fast |

Pain | Sensation of impact, less burning | Vibration, sensation of warm claws |

Ink saturation | Deeper and denser | Varies depending on the artist's hand |

Gradients (Bokashi) | Unparalleled subtlety, seamless transitions | Good, but less organic |

Aging | Keeps its shine longer (less blue-green tint) | May tarnish faster |

Healing | Often faster (less skin trauma) | Standard |

Cost | Higher (time × expertise) | Standard |

Availability | Rare (a few hundred Horishi in the world) | Everywhere |

Today, many masters combine the two: the machine for the main lines (Sujibori) and the Tebori for the fillings and gradations (Bokashi). Master Horiyoshi III of Yokohama — arguably the most famous living Horishi — contributed to this hybrid evolution while maintaining the spirit of the artisanal technique.

The traditional ink is Sumi (Chinese ink), made from pine soot and animal glue. Over time, under the skin, the black turns slightly blue-green: this is the famous "Irezumi Blue," a signature of old Yakuza tattoos. Modern artists also use colored pigments (Shu red, indigo, green, yellow), but Sumi black remains king.

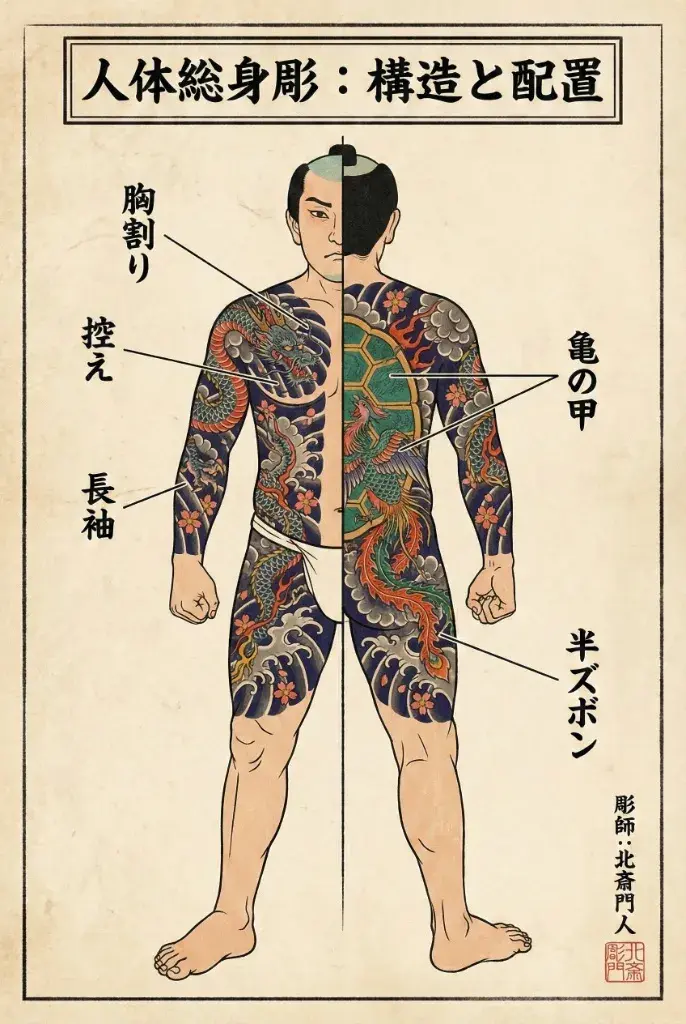

The Anatomy of a Bodysuit: Structure and Placement

An Irezumi is not a collection of randomly placed stickers. It is a body architecture with strict rules of composition, placement, and storytelling.

Main Formats

Format | Area covered | Special feature | For whom? |

Sōshinbori (総身彫) | Full body (shoulders → ankles) | The ultimate goal, 5 to 10 years of work | Absolute enthusiasts |

Munewari (胸割) | Back + arms + thighs, blank strip across the center of the torso | The most classic and elegant — invisible under a kimono | Traditional style par excellence |

Donburi (丼) | Full body WITHOUT central opening | The "turtleneck" of the tattoo | More modern, maximum coverage |

Hikae (控え) | Chest and arm panels | "Jacket" format | First major project |

Senaka (背中) | Full back only | The body's largest canvas | Centerpiece |

Gobu (五分) | Sleeves to the elbow | Discreet under a short shirt | Entering the Irezumi |

Shichibu (七分) | Sleeves extending to the forearm | The most popular today | Good compromise between visibility and discretion |

Nagasode (長袖) | Full sleeves down to the wrist | Strong commitment | Cosplay/art |

The Philosophy of Munewari: Hidden Beauty

The Munewari is the king of tattoos. This strip of untouched skin across the center of the torso is not a design flaw—it embodies the essence of the Edo Iki (粋) philosophy: true elegance lies in what is concealed. Beneath an open kimono or a work shirt, nothing is visible. The tattoo is for oneself, not for display.

The Gakubori: The Foundation That Does Everything

This is the fundamental difference between Japanese tattooing and all other styles in the world. In an Irezumi, the main subject (dragon, demon, carp) never floats in a vacuum. It is enveloped by the Gakubori (額彫り): a continuous background composed of natural elements.

background element | Japanese name | Symbolism | Visual role |

Clouds | Kumo (雲) | Celestial world, impermanence | Transition between motifs, framing |

Waves | Nami (波) | Force of nature, purification | Movement, dynamic energy |

Wind | Kaze (風) | Change, freedom | Wind bars that direct the gaze |

Rocks | Iwa (岩) | Stability, grounding | Base, foundation of compositions |

Lightning bolts | Inazuma (稲妻) | Divine power, Raijin | Dramatic accent |

Flames | Hi (火) | Purification, Fudō Myō-ō | Sacred Destruction |

These elements link the motifs together to form a single, coherent image that follows the contours of the body. You don't tattoo an image onto a body—you tattoo with the body. The waves follow the coastline, the clouds embrace the shoulders, the dragon coils around the arm as if it lived there.

Patterns and their Meaning: The Complete Dictionary

This is the heart of this article. Each motif has a history, a season, permitted and forbidden combinations. A good Horishi knows these rules by heart.

1. Mythological Creatures

Ryū — The Dragon (龍)

The undisputed king of motifs. The Japanese dragon has nothing to do with the fire-breathing Western dragon. It is an aquatic creature associated with wisdom, protection, and rain. It ascends to the sky to bring water, it descends to protect.

Dragon color | Meaning |

Blue/Black | Wisdom, depth, water |

Gold | Prosperity, wealth, imperial power |

Red | Passion, courage, fire |

Green | Nature, life, earth |

White | Purity, death, spiritual world |

Classic placement: Full back (Senaka) or sleeve wrapped around the arm. Associated background: Clouds + waves + wind. Do not pair with: A tiger facing the same direction (they must face each other — it's the cosmic duel Ryū vs Tora).

Tora — The Tiger (虎)

The eternal rival of the dragon. If the dragon reigns over water and sky, the tiger reigns over wind and earth. Together, they form the Ryū-Tora duel (龍虎), a symbol of the balance between cosmic forces.

Meaning: Brute strength, courage, protection against evil spirits and illness. Classic placement: Arm opposite the dragon, or thigh. Associated background: Bamboo + wind + rocks.

Hō-ō — The Phoenix (鳳凰)

The Japanese Phoenix is not a bird that rises from its ashes (that's the Western myth). The Hō-ō is a celestial bird that only appears when a virtuous ruler reigns. It symbolizes rebirth, triumph, and nobility.

Meaning: Rebirth, immortality, triumph over adversity. Classic placement: Back (often paired with a dragon or Kirin). Associated background: Paulownia (Kiri) + sacred flames.

Koi — The Carp (鯉)

The most popular motif in the world, but also the most misunderstood. Legend says that Koi carp swim up the Yellow River (Huang He) in China to reach the "Dragon Gate" (Ryūmon). The one that passes through the waterfall transforms into a dragon.

Meaning: Perseverance, ambition, transformation through effort.

Carp direction | Meaning |

Going upstream (upwards) | In the heat of battle, not yet transformed — effort, determination |

Going downstream (downwards) | Has already overcome the obstacle — success achieved, or abandonment depending on the interpretation |

Transforming into a dragon | Half-carp/half-dragon — the metamorphosis in progress |

Note: A koi carp swimming downwards is sometimes interpreted as "the one who has failed." This is a matter of debate among tattoo artists. Be sure to discuss the direction with your Horishi (artist).

Associated background: Water + maple leaves (Momiji) + splashes.

Shishi — The Lion-Dog (獅子)

Also called Komainu or "Foo Dog" in the West. This temple guardian is always depicted in pairs: one with an open mouth (A — the beginning), one with a closed mouth (Un — the end). Together, they form the sound "A-Un" (阿吽), the Japanese alpha and omega.

Meaning: Fierce protection, guardian against evil. Classic placement: Chest (in pairs), or thighs. Associated background: Peonies (Botan) — the Shishi + Peony duo is an absolute classic.

2. Masks and Demons

Oni — The Demon (鬼)

The most misunderstood motif by Westerners. The Oni is not a "villain." In tattoos, it's a terrifying guardian who punishes corrupted souls. Wearing an Oni is a way of saying: "I have the strength to fight my own demons."

Oni color | Meaning in the Irezumi |

Rage, passion, desire — the sins of the body | |

Coldness, calculation, hatred — the sins of the mind | |

Illness, doubt, laziness — the sins of the soul | |

Green | Blind anger, jealousy |

YELLOW | Regret, self-pity |

Traditional placement: Shoulder, arm, or as a central piece on the back. Traditional combination: Kanabō club + tiger skin (belt).

Hannya — The Mask of Jealousy (般若)

The Hannya is the Noh mask of a woman whose jealousy transformed her into a demon. It is one of the most powerful motifs in Irezumi. It does not represent "evil"—it represents the warning: uncontrolled passion destroys.

Meaning: Consuming passion, jealousy, but also the wisdom to recognize one's own darkness. Classic placement: Arm, thigh, or back (often with falling cherry blossoms). Associated background: Sakura (cherry blossom) + flames or smoke.

In my workshop, the Hannya is the mask I make the most. Tattoo artists buy myHannya masks to display in their shops — the direct visual reference between the physical mask and the design on the skin is powerful.

Tengu — The Heavenly Warrior (天狗)

The Tengu is the spirit of the mountains, master of martial arts. In Irezumi, it invokes martial discipline and protection against arrogance. It exists in two forms: the Karasu Tengu (crow) and the Daitengu (long nose).

Meaning: Martial mastery, humility, protection. Classic placement: Arm or back.

Kitsune — The Fox (狐)

The nine-tailed Kitsune is the messenger of the Kami Inari. It embodies cunning, magic, and prosperity. In tattoos, it is often depicted wearing a mask or undergoing human transformation.

Meaning: Intelligence, transformation, commercial prosperity. Classic placement: Thigh or arm.

Namakubi — The Severed Head (生首)

This motif shocks Westerners, but it is one of the oldest in Irezumi. A decapitated head, eyes open, sometimes biting a blade. In the Samurai code, accepting death is the key to courage. Wearing a Namakubi means: "I am not afraid to die" and "I will defeat my enemies."

Meaning: Memento Mori , bravery, victory over fear. Classic placement: Thigh, arm or side.

Fudō Myō-ō — The King of Wisdom (不動明王)

The supreme protector of esoteric Buddhism. He wields a sword to cut through ignorance and holds a rope to bind demons. His angry expression conceals infinite compassion.

Meaning: Ultimate protection, destruction of ignorance, devotion. Classic placement: Full back (absolute centerpiece). Associated background: Flames (Karyō) that always surround it.

3. Flora: The Seasons of the Body

In Irezumi, seasons are never mixed . A cherry tree (spring) does not coexist with a red maple (autumn) in the same composition. This rule is absolute.

Flower | Japanese name | Season | Meaning | Classic association |

Cherry | Sakura (桜) | Spring | Ephemeral beauty, short and beautiful life, the spirit of the Samurai | Wind, Hannya, Samurai |

Peony | Botan (牡丹) | Spring/Summer | Wealth, elegance, masculine courage (paradoxically: "King of Flowers") | Shishi (lion-dog), Dragon |

Chrysanthemum | Kiku (菊) | Autumn | Longevity, perfection, imperial flower | Serpent, Dragon |

Maple | Momiji (紅葉) | Autumn | Time passing, melancholy, transformation | Koi carp, water |

Lotus | Hasu (蓮) | Summer | Purity born from mud, spiritual awakening (Buddhism) | Fudō Myō-ō, Buddhist figures |

Snow peony | Kanbotan (寒牡丹) | Winter | Resilience, beauty in adversity | Rare — winter compositions |

4. Heroic and Historical Figures

The heroes of Suikoden (水滸伝, "Water Margin") and Japanese historical figures constitute a major category of Irezumi. These are the motifs that launched the explosion of tattooing in Edo in the 18th century, when the painter Kuniyoshi illustrated the 108 tattooed rebel heroes.

Figure | Meaning | Iconic detail |

Kintarō (金太郎) | The golden child, an innocent brute force | Fighting the giant carp, red skin, hatchet |

Demon slayer, courage | Cuts off Ibaraki Dōji 's arm | |

The King of the Oni: Excess and Destruction | Often shown in full back view, with a cup of sake | |

Minamoto no Yorimitsu (Raikō) | The Commander of the Four Heavenly Kings | Fight Tsuchigumo (the giant spider) |

Tamatori-hime | The diver who steals the Dragon's jewel | Naked woman among the waves, dagger, jewel |

The Rules of Composition: What a Horishi Never Mixes

Ruler | Explanation | Example of an error |

No mixing of seasons | Each motif belongs to a season. Sakura (spring) ≠ Momiji (autumn) | Cherry trees + red maples in the same sleeve |

The dragon and the tiger face each other | Ryū-Tora is a cosmic duel. They never look in the same direction. | Dragon and tiger on the same arm, same direction |

The fund is mandatory | No pattern floats in the void. The Gakubori binds everything. | A lone dragon without clouds or waves |

The subject dictates the content | Aquatic creature = waves. Celestial = clouds. Terrestrial = rocks | A dragon (water) against a background of waterless rocks |

Narrative symmetry, not visual symmetry | The back tells a central story. The arms are secondary chapters. | Two different backs (narrative inconsistency) |

Color has meaning | Red = passion. Black = depth. Blue = water. No arbitrary color. | A yellow Oni "because it's pretty" |

Japanese Tattoos and the Yakuza: Breaking the Myth

It's impossible to write about Japanese tattoos without addressing this topic. Yes, the Yakuza adopted the full bodysuit as a sign of commitment. Yes, it's because of them that tattoos are still prohibited in most onsen (hot springs), gyms, and swimming pools in Japan.

But here's the truth many don't know: modern Yakuza are getting fewer and fewer tattoos. Anti-gang laws (Bōryokudan Taisaku-hō) have become so strict that younger members avoid tattoos to avoid being identified by the police. Ironically, it's now foreign artists, musicians, and enthusiasts who are keeping the art form alive.

In 2020, the Supreme Court of Japan settled a historic debate: tattooing is an art, not a medical procedure . This decision paves the way for the cultural recognition of Irezumi as intangible cultural heritage.

My Opinion as a Craftsman: The Link Between Masks and Tattoos

I make Yokai masks. Tattoo artists are among my best customers. That's no coincidence.

Masks and tattoos share the same DNA: the iconography of Ukiyo-e (prints of the "floating world"). When I work on a red Oni mask , I use the same codes as a Horishi: the horns, the fangs, the Nirami expression (the petrifying gaze). The difference is that my medium is PETG, not skin.

Several tattoo artists have bought myHannya or Oni masks to decorate their studios. The effect is immediate: when a client walks in and sees a physical Hannya hanging on the wall, then sees the flash of the same Hannya in the tattoo artist's portfolio, the connection is made. The mask validates the design. That's why I created Dai Yokai : so that Japanese folklore lives not only in ink, but also in everyday objects, in my own way.

If you are a tattoo artist and are looking for an authentic decorative piece for your shop, take a look at the Hannya collection or the Oni masks .

Horishi Masters You Should Know

Horishi | Location | Speciality | Why it is important |

Horiyoshi III (三代目彫よし) | Yokohama | Traditional Tebori Bodysuits | The most famous living Horishi. Founder of the Yokohama Tattoo Museum (2000). Has trained dozens of apprentices. |

Horitoshi Family | Tokyo | Classic Edo style | A family lineage spanning several generations. Guardians of the most orthodox style. |

Horikazu (Asakusa) | Tokyo (Asakusa) | Pure Tebori, no machine | Considered one of the most "traditionalists" alive. |

Shige (Yellowblaze) | Yokohama | Neo-Japanese, hyper-detailed | A bridge between tradition and modernity. A major international influence. |

The traditional apprenticeship system (Deshi) still exists: the apprentice often lives with the master, does the housework, and prepares the needles for years before ever touching skin. He receives an artist name derived from that of his master: Horiyoshi → Horitaka → Horikitsune → Horisumi… It's a lineage, not a diploma.

Summary Table: 20 Motifs and Their Meaning

Pattern | Japanese name | Main meaning | Related element | Season |

Dragon | Ryū (龍) | Wisdom, protection, water | Clouds, waves | All |

Tiger | Torah (虎) | Strength, courage, wind | Bamboo, rocks | Autumn |

Koi Carp | Koi (鯉) | Perseverance, transformation | Water, maple | Autumn |

Phoenix | Hō-ō (鳳凰) | Renaissance, nobility | Paulownia, fire | Summer |

Lion-Dog | Shishi (獅子) | Fierce protection | Peony | Spring |

Oni | Oni (鬼) | Brute force, guardian | Club, tiger skin | All |

Hannya | Hannya (般若) | Jealousy, warning | Cherry tree, flames | Spring |

Tengu | Tengu (天狗) | Martial arts discipline | Mountain, feathers | Autumn |

Kitsune | Kitsune (狐) | Cunning, prosperity | Will-o'-the-wisp, mask | All |

Snake | Hebi (蛇) | Regeneration, protection, wealth | Flowers, skull | Summer |

Fudō Myō-ō | Fudō (不動) | Ultimate protection, wisdom | Flames, sword | All |

Cherry | Sakura (桜) | Ephemeral, short life | Wind | Spring |

Peony | Botan (牡丹) | Wealth, courage | Shishi | Spring/Summer |

Chrysanthemum | Kiku (菊) | Longevity, perfection | Serpent, dragon | Autumn |

Maple | Momiji (紅葉) | Melancholy, time | Water, carp | Autumn |

Lotus | Hasu (蓮) | Purity, awakening | Water, Buddha | Summer |

Head cut off | Namakubi (生首) | Memento Mori, bravery | Blade, blood | All |

Skeleton | Death, impermanence | Night, moon | All | |

Spider | Seduction, trap, deadly beauty | Canvas, flowers | Summer | |

Kappa | Water, dark humor, respect | River, cucumber | Summer |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the meaning of a Japanese dragon tattoo?

The Japanese dragon (Ryū) symbolizes wisdom, protection, and the power of water. Unlike the Western dragon, associated with fire and evil, the Ryū is a benevolent creature that brings rain and protection. Its color alters its meaning: blue for wisdom, gold for prosperity, and red for passion.

How much does a full traditional Japanese tattoo (bodysuit) cost?

A full bodysuit in Tebori (hand-pulled technique) costs between €15,000 and €50,000 depending on the master, the complexity, and the duration. The work spans 3 to 10 years, with weekly or bi-weekly sessions of approximately 2 to 5 hours each. It's an investment comparable to a luxury car—and a lifelong commitment.

Can you get an Irezumi tattoo if you're not Japanese?

Yes. Japanese tattoo artists (Horishi) have been tattooing foreigners since the 19th century—the future King George V of England got his tattoo in Japan. What matters is respect for the art: understanding the designs, accepting the pain, and not asking for incompatible elements to be mixed.

Why are tattoos banned in Japanese onsen?

The ban stems from the historical association between tattoos and the Yakuza (Japanese mafia). Since the Edo period, tattoos have been stigmatized. Today, most Japanese onsen (hot springs), swimming pools, and gyms refuse entry to tattooed individuals, even foreign tourists with small designs. Some modern establishments are beginning to relax this rule, especially in tourist areas.

What is the difference between Tebori and machine tattooing?

Tebori is the traditional Japanese hand-inking technique: the artist inserts ink under the skin using a handle and needles, stroke by stroke. It is slower but produces more subtle gradations (Bokashi) and more stable aging. Machine ink is faster but less nuanced. Today, many artists combine the two techniques.

Comments